Busting up and deeply personal national traumas

AKA: the “disgusting and opportunistic farce”

of version 1.0’s From a distance… (2006)

Introduction

In the women’s rowing eight final at

the Athens Olympic Games in 2004, Australian rower Sally Robbins stopped rowing

before the finish line. Immediately following the race, the team very publicly

busted up, held a press conference in which they declared that they had

reconciled, and then very publicly busted up again. Concurrently a highly

emotive debate began in Australia about how this rowing failure might reflect

upon and illuminate the national character, triggering a lengthy debate about

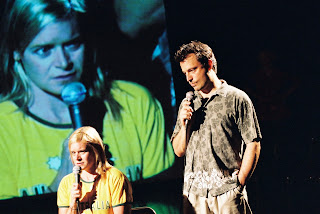

national identity and values. In late 2005, Sydney-based performance group

version 1.0, a company of which I am a member, began work on a performance

about this debate, taking the so-called ‘no-row’ incident as a starting point.

Very soon after commencing work on the project, version 1.0 began receiving

threats of legal action and hate mail that memorably declared that the project

was “a disgusting and opportunistic farce”. This paper will begin by briefly

outlining the incident and the deeply emotive responses that this incident

provoked, then begin to unpack the values at the core of this notion of the

un-national, and then finally begin to consider what might animate version

1.0’s theatrical representation of these deeply intertwined personal and

national traumas.

Part 1.

For those of you who managed to miss

the incident when it occurred, here’s a brief summary of what happened. For

reasons still hotly debated, rower Sally Robbins stopped rowing 600 metres

before the finish line, slumping back in her seat. Upon finishing the race, the

other crewmembers verbally abused Robbins, with one of her team-mates declaring

that: “I just want to stress there was not a technical problem. No seat broke.

There was nothing wrong with the boat. We had nine in the boat but only eight

operating. That’s all I’m going to say.” Other crew members were recorded by

media yelling out: “Tell the truth Sally! Don’t lie!” Robbins herself commented

to Channel 7 that: “I had some pretty hard words thrown at me. I had some

pretty tough things to take,” and also claimed that her teammates had

threatened to throw her overboard.

The mood back home in Australia was

similarly hostile. Cathy Freeman, herself no stranger to nationalistic

controversy, stated that: “From a distance, to give up is almost very

Un-Australian.” Ron Barassi was less subtle, stating: “You don’t quit until

you’re unconscious. She wasn’t thinking about her team, and she wasn’t thinking

about her country.”

The team held a press conference the

following day, facilitated by AOC President John Coates, where they repeatedly

insisted that they had reconciled, yet the following day team members were

again venting to the media. At a welcome home function in Sydney, Robbins was

slapped by one of her team-mates, and then it was reported that the rift continued

when Robbins was a no-show to the wedding of Julia Wilson, the team captain.

The media loved the story, and it became a strange sort of grubby soap opera.

Recently, Robbins tried and failed to seek selection for the Beijing Olympics,

which provided an excuse to run through the story all over again on newspaper

front pages. According to one recent report, she is now considering a career in

cycling.

Part 2.

Freeman’s use of the term ‘unAustralian’ to describe this

incident was far from isolated, with ‘un Australian’ appearing regularly in the

commentary on all aspects of the ‘no row’ incident. Robbins was un-Australian

for quitting. The rest of the team was un-Australian for turning on her.

Athletes had become un-Australian for overturning apparently long-held values

of sporting conduct. The commentators were un-Australian for getting stuck into

someone in such a moment of weakness.

In their paper Popular

understandings of ‘UnAustralian’: an investigation of the un-national

(2001), sociologists Phillip Smith and Tim Phillips observe that unlike the

long standing usage of the term ‘UnAmerican’, there appears to be no clear

definition of notions of un-nation in an Australian context. Unlike the use of

the term UnAmerican to indicate an apparent betrayal of national values and

ideologies, those historical references that do appear to UnAustralian-ness

have distinct racial characteristics. UnAustralian seems to equate historically

with non-white, though more contemporary usages seem to cluster around concepts

of values. Noting the exclusionary function of the term, in the conclusion of

their paper they begin to explore the possible motivations animating this

exclusionary impulse. Drawing on the work of Zygmunt Bauman they note that this

naming process forms part of a response to anxieties and feelings of insecurity

about rapid social change:

“Labelling an object or event

‘UnAustralian’ is a core aspect of the boundary- maintaining process: blaming

‘out-groups’ for change and the decline of ‘the old ways’ (Bauman, 1990: 48).

We might expect this more aggrieved usage of the ‘UnAustralian’ to be part of a

larger vocabulary of motives found mainly to be concentrated in the life-world

of a ‘middle Australia’ (Brett, 1997) reacting to the perceived threat to their

symbolic-moral universe.” (Smith and Phillips 2001: 337)

It is this use of the term

un-Australian to control a perceived threat to a symbolic moral universe that

animated the performance project From a distance....

Part 3.

In late November 2005, Victoria Laurie, a journalist with

the Perth desk of The Australian newspaper, discovered whilst browsing the

internet that version 1.0 was planning on making a performance about the

so-called ‘no row’ incident. Due to the fact that the rower at the centre of

the scandal was based in Perth, Laurie thought that this was a good basis for a

story. No doubt some of her interest was piqued by the unintentionally

sensationalist proposed title of the work: Sally Robbins: An UnAustralian

Story.

Whilst perhaps not as insensitive as

the title of Dan Illic’s recent Beaconsfield: A Musical in A Flat Miner,

planned as part of the 2008 Melbourne Comedy Festival, the placement of

Robbins’ name next to term un-Australian proved extremely problematic, despite

the originally intended title never being publicised. As part of her news

story, Laurie contacted Robbins for comment. While declining to comment for the

story, Robbins was reportedly unamused in the extreme, and immediately

contacted her lawyers, who in turn contacted version 1.0.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, those who

spend so much of their lives striving to achieve the authorization to represent

Australia in domains such as sport are quite sensitive to the means by which

their representation is subjected to further representation in other domains.

Robbins was extremely unhappy with what she and her legal team believed was the

show’s primary assertion that Robbins was Un-Australian, despite the fact that

the show never intended on making such an assertion or implication, being more interested

in the fact that others made such assertions, and further interested in

exploring what this might mean for our national identity. Neither Robbins nor

her legal team recognised the distinction. This is a marked contrast to the

response of elected representatives in the domain of politics, the subjects of

other performance work by version 1.0, who appear far less concerned about

their potential representations in domains other than their own. It has been

suggested by my less charitable colleagues that this is because politicians are

essentially vain, though such an assertion is of course impossible to quantify.

Lawyers representing Sally Robbins

began issuing threats of legal action, initially framing their concerns around

the proposed title of the project. After largely amicable negotiation with

Steve Lawrence, Executive Director of the Western Australian Institute of

Sport, representing Robbins’ lawyers, the official title for the production

stage of the project was altered to From a distance…, an acceptable

compromise title. However, Robbins’ lawyers remained interested in pursuing

defamation actions against the company, continually asking for a copy of the

script so they could approve it. Legal advice obtained by version 1.0 indicated

that Robbins’ lawyers had no rights to gain a copy of the script, which at any

rate did not yet exist, and strongly advised against providing one to her legal

team on the grounds that it could be used as the basis for a defamation action.

These later negotiations were often extremely tense.

The title was intended to be highly

ironic, and to draw attention to the rhetorical over-reaction of commentators

and members of the public to the incident. It was not intended to be a comment

on the Australian-ness or other wise of any individual, though this made little

sense to anyone beyond the members of version 1.0 at that stage. Laurie, and

other journalists after her seemed convinced that the performance must include

a reenactment of the race, and must also make some contention about who might

be to blame. Of course, the intended project was designed to do neither of

these. As I attempted to explain in an email to Steve Lawrence:

“There’s a couple of mis-conceptions

that may have arisen as a result of the recent media reportage of the proposed

performance that I should address at this point. Media, as you know, does tend

to mis-represent. In the performance, we do not ‘re-enact’ any part of the

incident, not any part of the race, and not the incident at the welcome home

event. The only ‘re-enacting’ in the performance is of the press conference,

and that’s simply in terms of repeating the words that were said there. There

are references to these incidents, but not re-enactments. We assume that the

audience already knows what happened, and what we explore is the reaction to

the incident, and what that (over)reaction might tell us about our national

identity. I know that sounds abstract, but my point is that none of this is

personal.” (email 16 December 2005)

As I’ve noted elsewhere in regards

to re-enactment, version 1.0 has tended to focus on re-presenting the aftermath

and reactions to events rather than re-enacting the events themselves – staging

questionable second order reproductions rather than faithful copies. This is

especially true in attempts at re-presenting events for which there was in fact

no original, such as the so-called ‘children overboard’ affair of 2001, the

subject of version 1.0’s 2004 work CMI (A Certain Maritime Incident).

Laurie’s article, ‘Lay Down Sally,

the stage play’ (published 8 December 2005), provoked demands for interviews

from media outlets nationwide. This media interest in the project also provoked

hate mail directed at the project artists, an edited version of which was

included in the show. The hate mail challenges the right of artistic practice

to represent real events, and posits arts attempt to represent such events as

an act of violence.

“I felt I should write and let you

know of my disgust upon hearing of plans for the play; truly a concept that is

shit-to-the-core with bad taste, bad timing, and has an overwhelming stench of

useless arty-farty endeavour. These are not fictional stereotyped characters,

nor is this a generalised sporting situation of triumph and tragedy that needs

to be performed as an interpretive bloody dance. It is a real story that

occurred in the not-so-distant past, and involved real thinking, feeling,

emotional people, who are still around today, and in many cases are trying to

continue with their careers. […] Would you acting-types like it if I wrote an

analytical book about the time you were dining with the Premier and your beret

fell off your head into your skinny latte? […] In closing, a general fictional

play on the subject would be fine. Perhaps even a very similar situation, but

in a different sporting field? But a specific performance of a very recent and,

for many people, very tragic situation, involving people that are still trying

to go about their lives, is indeed a disgusting and opportunistic farce. Shame

on you.”

The email is not a response to the

performance itself, but rather a response to the idea that such a work might be

made at all, a response to “hearing of plans for the play.” Nonetheless, the

letter effectively marshals a range of Australian cultural anxieties around

artistic practice, and adds to this a fascinating illustration of the deeply

personal stakes of this incident, even to uninvolved spectators. Of course, one

email is undoubtedly a scant evidentiary basis for such an assertion. It was

however my experience when talking about the ideas for the show in a range of

social contexts, that it was extremely rare for the person that with whom I was

talking to not have strong opinions about the incident.

One possible reason for this

personal and visceral reaction is the incident is seen as a crisis of values –

a fracture in the symbolic moral universe that Smith and Phillips discuss that

requires urgent repair. As if anticipating this need for repair, around the

same time as the ‘no row’ incident, former Prime Minister John Howard proposed

a list of seven core national values shared by ‘ordinary Australians’. Howard

stated at the time that:

“A sense of shared values is our

social cement. Without it, we risk becoming a society governed by coercion,

rather than consent. That is not an Australia that any of us would want to live

in.”

His list of shared values were:

- We live in a very successful nation.

- We do not have much to be ashamed of.

- Australia is well-regarded around the world.

- Individuals should be given a fair go if down on their luck but, once helped, should not expect continued community support.

- Traditional institutions like the family are central but people with alternative views should not be persecuted.

- Society should be classless where a person’s worth is determined by personal character and hard work, and not religion, race or social background.

- People should be very tolerant, but also believe in unity when facing a common threat.

It is the symbolic moral universe articulated in this list of values that in some way begins to make sense of the excessive reaction to the ‘no row’ incident that led to a 23-year old athlete being widely branded ‘un Australian’ for stopping in a rowing race. The performance From a distance… attempted to make sense of this national identity crisis by tracing what the nation says it isn’t. We live in a very successful nation. We do not have much to be ashamed of. There’s clearly a much more detailed discussion that needs to be undertaken around the largely negative orientation of many of these values, not to mention the significant caveats that this list contains, but unfortunately that is beyond the scope of this paper.

The hate mail contained some further

useful warnings about the care required when investigating this territory:

“Sure, the event was controversial,

and raised questions about what was acceptable conduct in the sporting arena.

Maybe it was a reflection of some deep-rooted aspect of being Australian? Who

flamin’ knows?! Perhaps these issues should be explored, but this incident

should not be used as some sort of “type-example” or snapshot of the Australian

psyche, because you have no understanding of the inner workings of the team,

the personalities at play, the prior history, the pressure of the situation etc.

To put it forward as a study of “un-Australian” behaviour (or whatever),

without having full knowledge of the situation is ludicrous and, as stated

above, in very bad taste…shit taste in fact.”

The impertinence of this performance

project is that it uses this incident as a trigger to investigate the territory

of the un-national, despite the warning contained in the hate mail. Obviously

to fully articulate the ways in which any performance might achieve such an

undertaking requires far greater space than is available in this paper, and

indeed I would suggest that From a distance… was far from successful in

its performative investigation. Despite its flaws however, this work was

intended as an act of critical patriotism, and perhaps such a motive can at least

partially excuse such “a disgusting an opportunistic farce”.

David

Williams

Paper

delivered at the ADSA Annual Conference, Edith Cowan University, Perth, July

2009

Comments